History

Academies of science around the world

In Ancient Greece, the word academy referred to a school, but it gradually came to mean higher education. In Renaissance Italy, academy was already established to mean a society of educated people, referring in particular to the regular meetings of scholars of Latin and Italian.

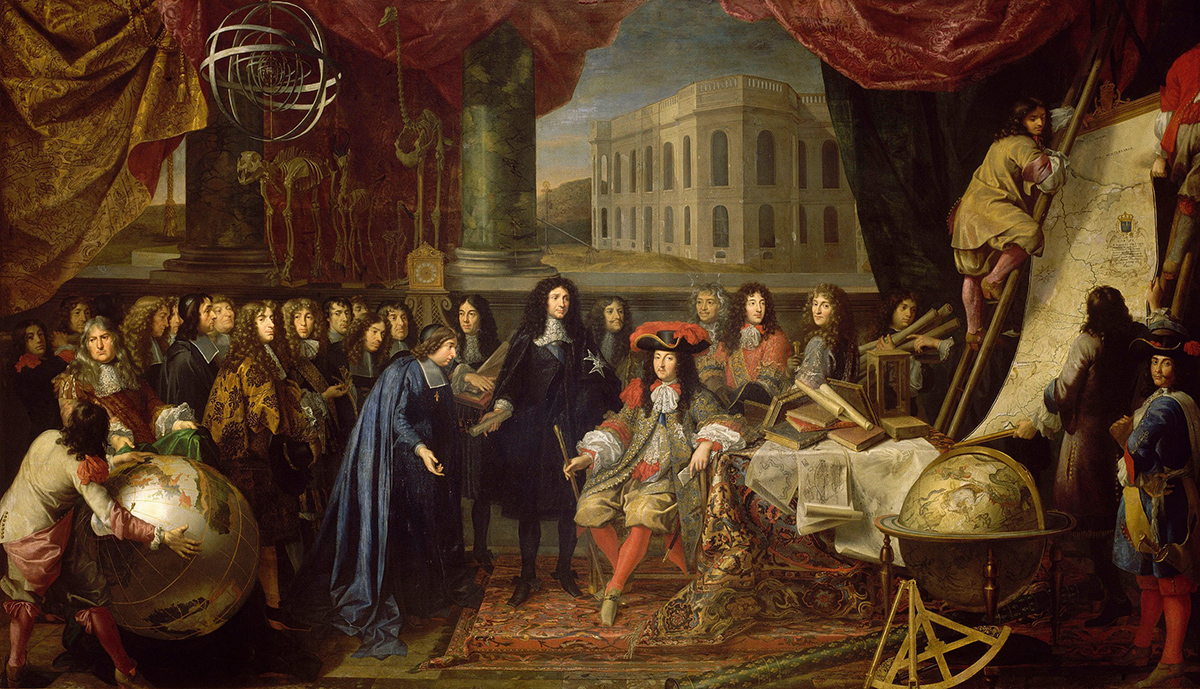

In the 16th century, scientists with modern ideas broke away from the Catholic Church and the universities that shared its world view. Much of the active and innovative scientific research took place outside the universities, and the regular meetings of scientists gradually became institutionalised as academies of science. Accademia dei Lincei, founded in Rome in 1603, and Académie française, founded in Paris in 1635, are the oldest models for modern academies.

Originally, academies focused on either mathematics and science or the humanities, but in the next century so-called universal academies emerged to challenge this dichotomy.

The 18th century was the century of the academies: they became an institutional movement throughout Europe. By the time of the French Revolution in 1789, there were already 70 academies of science in Europe. The popularity of academies stemmed from the rationalism and optimism of the Enlightenment, but it was also often a way for rulers to present themselves as educated.

Academies in the world:

- Académie française (1635)

- Academia Naturae Curiosorum, nyk. Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina (1652)

- Royal Society (1662)

- Académie des sciences (1666)

- KungligaVetenskapsakademien (1739)

- Svenska Akademien (1786)

- Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab (1742)

The Finnish Academy of Science and Letters

The Finnish Academy of Science and Letters was founded in 1908. This was a result of the language policy between Finnish and Swedish, the growing number of educated Finnish speakers and the general political climate of the late 19th century.

In the late 19th century, the Finnish language had become a language of scientific standards, with more widespread use and an evolving vocabulary. Thanks to the Fennoman school policy and other civic education efforts, the number of Finnish-speaking students at the Imperial Alexander University (University of Helsinki) grew rapidly. The new students were overwhelmingly Finnish-speaking. However, teaching in most faculties and departments was still mainly in Swedish, which created tensions within the scientific community.

In the 19th century, several scientific societies were founded, such as the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim in 1881 and the Finno-Ugrian Society in 1883. In 1838, the Finnish Science Society covered all scientific disciplines. However, by the end of the 19th century, the Society was known mainly as a society of elderly Swedish-speaking professors, and Finnish-speaking members were in the minority.

The Russification policy of the Russian Empire polarised Finnish politics in the late 19th century, which affected the scientific societies and the selection of new members. Exclusion from a prestigious scientific society was a matter of great concern to many professors with a more moderate attitude towards Russia.

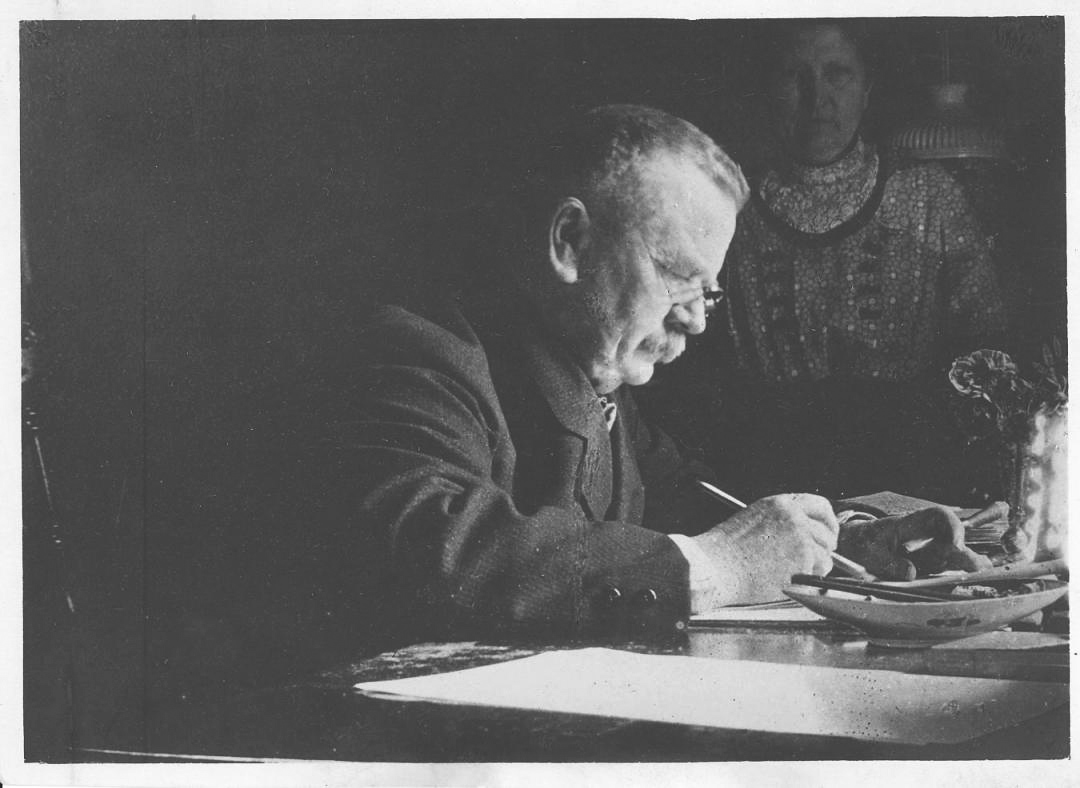

In the 19th century the Imperial Academy in St. Petersburgh held the exclusive right to be the one true academy of science in the Russian Empire. In 1906 Tsar Nicholas II confirmed a law allowing freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, and freedom of association, which made it legally possible to establish a new academy of science. The Finnish Academy of Science and Letters was founded in 1908.

Eliel Aspelin-Haapkylä, Professor of Aesthetics and Contemporary Literature, was elected as the first President of the Board. The Academy’s first Secretary General was Gustaf Komppa, Professor of Chemistry, up until year 1944. The Academy decided to divide itself into two sections: science and humanities.

Histories of the Academy

Oiva Ketonen

Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia 1908-1958

Helsinki 1959. 338 pp.

Aimo Halila

Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia 1908-1983

Helsinki 1987. 291 pp.

Jyrki Paaskoski

Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia 1908-2008

Helsinki 2008. 447 pp

An abbreviated version of the latter has also been published in English:

Jyrki Paaskoski

A community of Scholars. The Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, 1908-2008

Helsinki 2008. pp. 95

The Heads and Secretary Generals of the Academy

The Chairs of the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters The secretaries/Secretary Generals The Chairs of the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters Tuula…