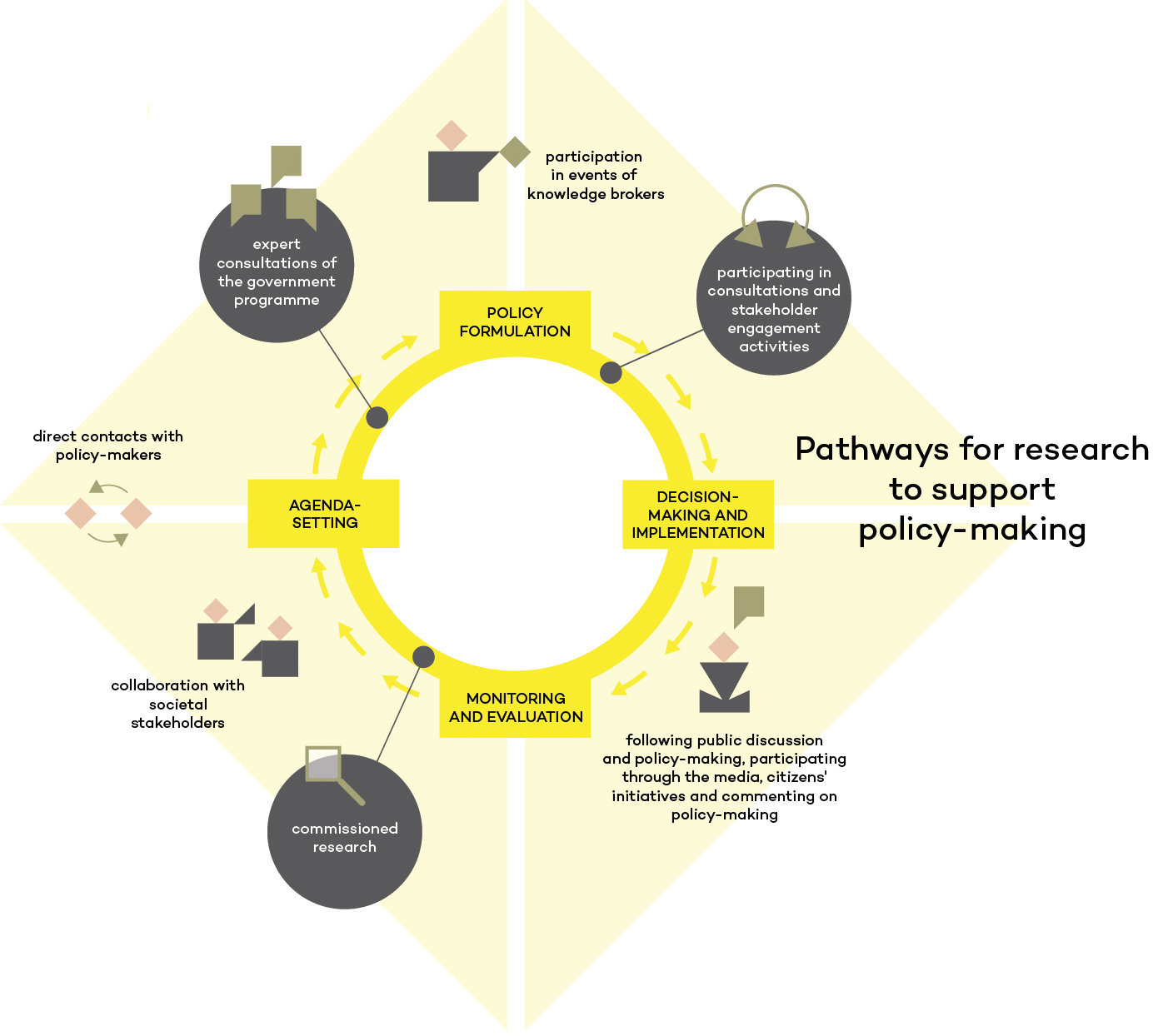

Part 3. Pathways for research to supporting policy-making

The duties of policy-makers differ from each other, as do their needs for research knowledge.

Members of parliament:

- A significant portion of the work of members of parliament takes place in committees where reports are drafted on government proposals concerning laws or state budgets, for example. In plenary sessions, members of parliament convene to discuss and jointly vote on these government proposals based on the reports. Members of parliament also participate in government negotiations and they can initiate the drafting of new legislation with a parliamentary statement, for example.

- Members of parliament utilise research knowledge in their committee work, for example. They also have assistants whose job it is to provide the members of parliament with information they need for their work.

Civil servants of ministries:

- The roles of civil servants in ministries vary. The duties of some civil servants have more to do with preparing and supporting policy-making while others focus more on recruitment or maintaining the operations of the ministry, for example.

- When preparing policy, civil servants draft laws and strategies, listen to stakeholders and evaluate the effects of planned measures.

- In their work, civil servants utilise research knowledge to expand and deepen the knowledge base of the drafting process.

Municipal policy-makers:

- Municipal policy-makers refer to elected officials and office holders working in municipal councils and local government. Persons working in crucial committees who are not members of the municipal council can also be counted among municipal policy-makers.

- Office-holders utilise research knowledge when drafting municipal decisions, strategies and action plans. For their part, elected officials utilise research knowledge especially when considering their positions on the matters discussed in the decision-making bodies (committees, government or council).

Policy-makers of well-being services counties:

- Policy-makers of a well-being services county consist of representatives from the local council and members of the local government who are in a position of trust and thus responsible for the operations and finances of the well-being services county wielding the county’s highest authority. The director of the well-being services county is also counted among the county’s policy-makers. The director is a subordinate of the local government and leads the administration, finances and other operations of the well-being services county.

- Members of the local council and government view research knowledge from the perspective of their own region and utilise it when applicable. The director of the well-being services county can utilise research knowledge as the foundation of the strategic development of the county, for example.

The various levels of policy-making (national, regional and municipal) describe the distribution of authority in Finland. The levels also represent different kinds of audiences for research knowledge and different cooperative partners for researchers in the various spheres of policy-making. Next we will focus especially on policy-making on the national level (members of parliament and civil servants of ministries).

The political decision-making of the government has various stages

At the centre of political decision-making on the national level is the government, which aims to realise policy measures in accordance with its programme. Examples of policy measures include the government’s budget decisions, proposals, pledges, strategies, reforms and programmes.

The government’s decision-making can be divided into various stages. The stages are often described as a cycle of politics where the stages take place after each other.

- For the government, the stage of setting the agenda takes place in the government negotiations where the parties discuss the contents of the government programme, i.e., the action plan for the term of office. The government programme will contain all of the government’s central goals and measures for the term, such as addressing biodiversity loss or ensuring that more nurses are being trained. Stakeholder groups and specialists are also heard during the negotiations. Their interests and perspectives can be utilised in drafting the items in the government programme. Of course, the negotiations as a whole are based on the political programmes of the parties, in which the parties have already stated their own agendas.

- In the drafting stage, the civil servants from ministries survey, plan and work on policy measures that can be implemented to achieve the goals laid out in the government programme. The civil servants draft laws and strategies, for example, and plan the allocation of funds to measures that aim to promote the reaching of the goals. The civil servants draft these measures into government proposals, which are then discussed in parliament. If the parliament approves the proposal, the implementation of the policies begins.

- In the implementation stage the policies are put into effect. This is the responsibility of public administrative bodies such as municipalities or the offices and departments subordinate to the ministries. The policies can either obligate (e.g., law), economically steer (e.g., budgetary appropriations) or inform (e.g., communication campaigns and instructions) societal operators.

- In the stage of monitoring and evaluation, the ministry responsible for the policy-making evaluates the impacts the law or other policy has had. In this stage the policy can be deemed appropriate or drafting work can begin on the changes it requires.

Different inputs are expected from research knowledge at different stages of policy-making

Below the different stages of policy-making are discussed in more practical terms from the perspective of a legal reform and the research knowledge related to it.

The drafting of a new piece of legislation or a legal reform begins with a motion. A motion can be based on an item in the government programme, a bill proposed by a member of parliament or a popular initiative.

- Research knowledge can have an impact in the background if researchers had been heard on the topic of the motion during the government negotiations. Research knowledge might have also informed the motion if the researchers have published their writings in the media and this spurred members of parliament to bring the topic or perspective into the government programme. The researchers themselves can also participate in starting a popular initiative on a topic they consider important while leaning on research knowledge.

The ministry responsible for the subject matter of the motion initiates preliminary drafting. At this stage, information about the goal of the motion is gathered, the need for initiating a legislative project is evaluated and its implementation is planned. Ultimately, the minister responsible or the leading civil servants decide whether the motion results in the initiation of a legislative project.

- The civil servants of ministries listen to researchers and utilise research knowledge when charting what is known about a topic, identifying the central challenges related to the topic and when evaluating the need for a legislative project, for example.

Then the motion proceeds to the primary drafting stage where the knowledge base is expanded, solutions to questions arising during the drafting are pondered and the effects of new sections of law are evaluated. The drafters write the legal text and the justifications for it to form a draft of the government’s proposal. If the proposal is approved (the minister or leading civil servants can decide on approval), the process proceeds to the next stage.

- Research knowledge is utilised and researchers are heard during primary drafting when forming an understanding of the status quo related to the legislation and evaluating the possible impacts of the amendment. Basic drafting can also involve external surveys that researchers participate in.

After primary drafting, stakeholders are heard regarding the drafts of the government’s proposal. Besides those stakeholders deemed central to the issue, other stakeholder groups may also issue written statements on the lausuntopalvelu.fi platform.

- At this stage, researchers might receive direct statement requests from the ministry responsible for the matter. Additionally, researchers can also present written statements concerning the proposal in its entirety on their own initiative.

The next stage is further drafting where the drafters use the statements as the basis for making the changes to the proposal decided on by the minister, leading civil servants or the government. The law is also reviewed at the Ministry of Justice, after which the motion is finalised and ultimately approved for presentation to the government. In a general assembly, the government then decides on referring the motion to parliament.

- Research data can be utilised when making changes to the motion and researchers can be heard considering the possible effects of the changes.

A plenary session of parliament decides on moving the proposal into the committees. The committees form a report on the proposed law that contains the committee’s views on the law and proposition on whether to accept, reject or alter it. To support the formation of the report, the committees hear from various stakeholders and civil servants of ministries.

- Researchers are also invited to be heard if the committee believes that better understanding from various perspectives is required to form the report.

Then a discussion is had in a plenary session concerning the legislative proposal based on the committees’ reports. In these discussions the law is thoroughly scrutinised and possible proposals that differ from the reports are made to the legislation. Finally, a plenary session of parliament votes on whether to accept or reject the law. Then the law proceeds to implementation and the ministry responsible for it begins to assess its impacts.

The routes by which research knowledge can reach policy-making are more diverse than people often think

Even with a single legislative reform, the pathways research knowledge can take to support it are diverse, but the opportunities to make an impact do not stop there. Furthermore, not every route to promoting the societal impact of research is directly connected to a certain stage of policy-making and some of them represent interaction directed outside of policy-making. Some of these opportunities are listed below.

Direct contact

In Finland, the hierarchies between policy-makers and citizens are low. For example, a researcher can contact a member of parliament and offer summarised research knowledge independently or together with other researchers at junction points significant for policy-makers, such as during the drafting of a party’s programme or when parties move into opposition as a result of the formation of a new government. Municipal policy-makers and civil servants of ministries can also be contacted when a drafting process is ongoing that connects to the researcher’s expertise. Staying in contact also enables the formation of longer-term relationships.

Following public discourse and policy-making

Lausuntopalvelu.fi and otakantaa.fi list the drafting processes currently ongoing in the government and municipalities. For policy-making on the level of the European Union there is the Have your say service. These services allow people to express their views on drafting processes that have moved to the statement stage (e.g., what the proposed solution looks like in light of research knowledge, or what should be especially considered in the drafting process). Furthermore, the government’s website contains a list of all the regulatory drafting processes and development projects in progress during the government’s term (valtioneuvosto.fi/hankkeet). The listed projects might not have yet reached the statement stage. By following these websites you can keep up with current policy-making and think of the right time to offer your expert perspective in writing, for example.

Participation in events held by knowledge brokers

Various scientific panels (the Finnish Expert Panel for Sustainable Development, Climate Change Panel, Nature Panel and the Forest Bioeconomy Science Panel), the Forum for Environmental Information and the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters provide opportunities for encounters between researchers and policy-makers. In other words, promoting the societal impact of your research can also occur via an intermediary. The work of knowledge brokers is facilitated when the researchers’ contact information is up-to-date on the university website, for example. This makes it easier for the brokers to find the right researchers to interview or participate in workshops or seminars.

Channelling knowledge to stakeholders outside of policy-making or cooperation with such stakeholders

In addition to or instead of policy-makers, the interaction can also be directed at other stakeholder groups, such as companies or trade organisations. You could, for example, organise a meeting with the organisations or be in contact with companies offering them summaries of your most recent observations. The research knowledge might then be considered in policy-making through these operators.

Researchers could also cooperate more closely with various stakeholders by participating in the activities of politically independent organisations, for example.

The slow crawl of knowledge through society

The impact of research knowledge is also built through the slow crawl of knowledge. This means that citizens come to gradually understand the research knowledge as the research observations and themes are kept in the public eye. This way research knowledge can gradually affect voter behaviour or become included in the drafting work of municipal policy-makers, for example.

Tip: Understanding the stages of policy-making also brings better understanding of the needs of policy-making. Conceptualising your opportunities to make an impact might be easier if you know whether the process is at the agenda setting stage where matters important for the next tenure of government are discussed or whether the drafting work of a ministry is halfway complete and the consideration focuses on the impact of various alternatives. Having an understanding of the role of the policy-maker and the topic related to the policy makes it easier for you to form the perspective for messages concerning your research area. For example, as an expert of sustainability sciences you could choose to focus solely on social sustainability or that you apply research knowledge to meet the needs of the day on the municipal level.

Policy-making is about much more than research knowledge

The pathways and routes research knowledge takes to find its way into policy-making are numerous and the societal impact of the knowledge can be promoted in various ways. Additionally, policy-making requires consideration of other factors as well. For example, the goals set out in the government programme form the starting point for the government’s policy-making, and various stakeholders, not just scientists, are extensively heard when these are being implemented.