Part 4. Researchers’ pressures and strategies in impact work

To begin this section, think about the following:

- Have you participated in the promotion of the societal impact of research in your work?

- If yes, how have you promoted the impact of research and with whom?

Many researchers actively participate in a diverse range of stakeholder activities via various projects, for example. Furthermore, all researchers participate in education work in some way, which is a significant pathway to societal impact: students pass on what they learn into working life. Some researchers visit upper secondary schools, organise other popularised lectures or teach via YouTube videos, for example.

The purpose of this course is not to pressure anyone into increasing the amount of impact work. Instead, it might be beneficial for the researcher’s work and use of time to recognise the various opportunities for interaction.

There are means to process the expectations related to societal impact

The work of a researcher is difficult and there are a lot of pressures related to progress on the scientific career ladder. The work is also self-guided and the pressure to publish frequently is high. Furthermore, the employment relationships are often fixed-term and there is a feeling of uncertainty concerning future prospects.

Especially in the early stages of one’s career, working conditions can make it more difficult for the researcher to orientate toward societal impact work. The complexity involved in the societal impact of research and providing support for policy-making brings its own challenges to the equation.

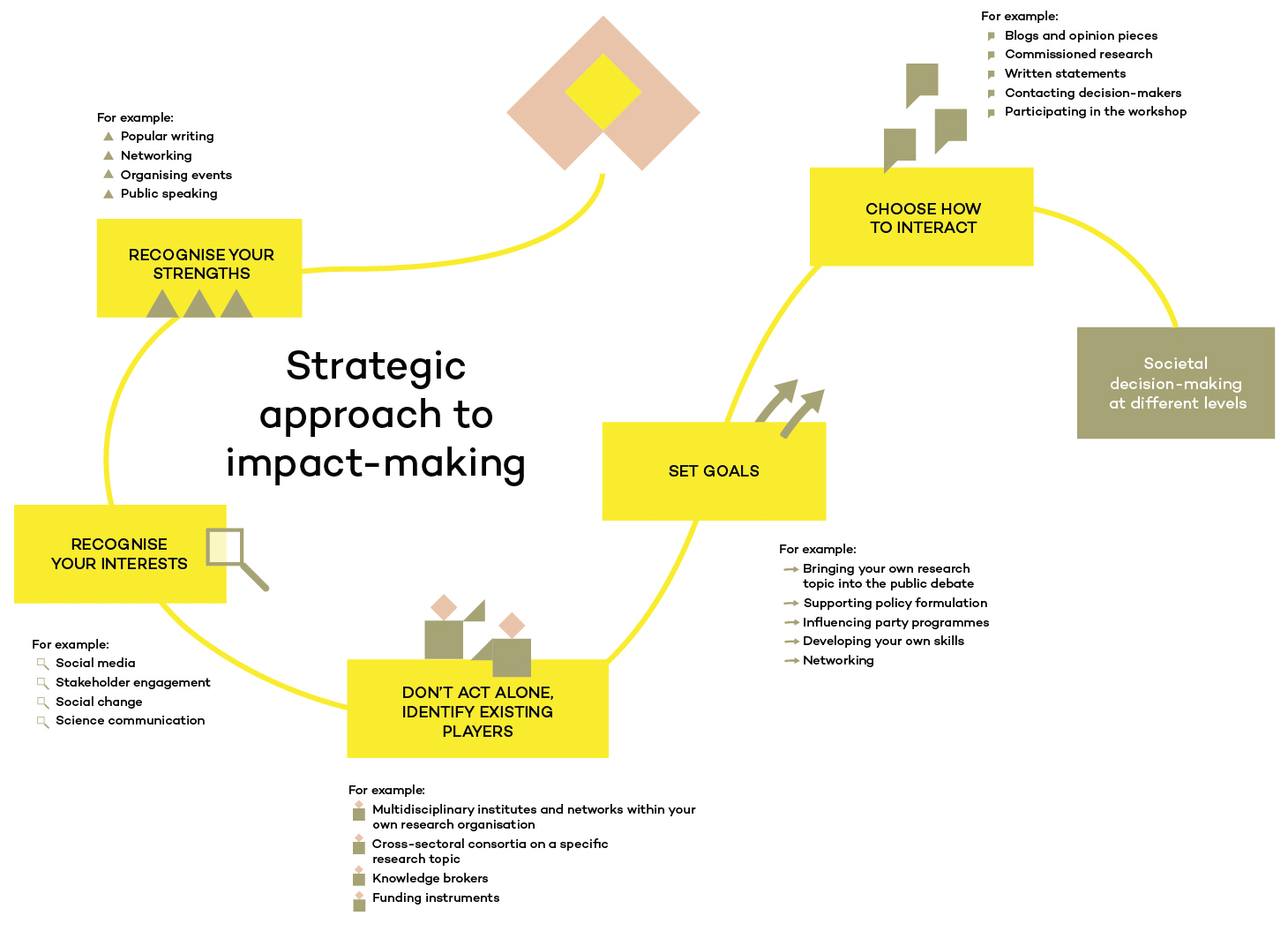

It is thus understandable that as a whole the topic might seem burdensome to the researcher. Where could a young researcher begin? How is it possible to manage these pressures? The following approaches might be helpful, for example:

- You could begin with your own strengths and interests.

- Strive to identify existing operators, i.e., do not work alone.

- Strive to set goals and choose the means of interaction that correspond to the goals.

Next, we will discuss these approaches in more detail. You get to delve into the planning of your own actions in the next and final section of the course.

Outlining one’s own strengths and interests forms a solid foundation for impact work

Identifying your own strengths helps you find low-threshold ways of starting to promote the societal impact of research and building paths toward policy-making. If you think you have a handle on summarising your own research results into social media posts, they might be a good place to start. If working in your own comfort zone begins to feel boring, it might be time to try something else, such as contacting a municipal policy-maker or presenting an offer of cooperation to a local organisation.

The researcher’s interest can be connected to societal issues, such as growing inequality or the technical development related to the green transition, for example. The researcher might also be interested in the means of interaction, such as writing a personal blog or the building of networks.

One’s own interests are a good starting point for impact work as they provide motivation. When you take action based on your own interests, it also makes is easier to learn new things. Motivated activities can open up new opportunities later on and encourage you to try something new: blog posts can provide a solid foundation for writing a popularised book, and the strengthening of networks can encourage you to channel knowledge to a ministry.

Working together with others decreases pressures of a researcher

Even though it is useful for researchers and primarily important for their motivation to identify the starting points for one’s impact work, you should not go at it alone. When you cooperate, you get to share your experiences of success and frustration together with colleagues. It also reduces your own workload and the messages might carry more weight with more researchers behind them.

However, support and guidance are not always available from one’s immediate colleagues or even in one’s own faculty. In such events it might help to expand your search to existing platforms, networks and collectives to support your impact work. Unfortunately, the researcher is often left to find these operators on their own.

Relevant operators can be identified on at least the following levels:

- Institutes and networks of the research organisation, such as a university (e.g., HELSUS)

- Thematic research networks of the scientific community (e.g., YTF)

- Consortiums of researchers and societal operators (e.g., Urban Academy)

- Operators specialising in knowledge brokering (e.g., the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters)

- Financial instruments (e.g., the Strategic Research Council)

Setting your own goals may help select suitable methods of interaction

In impact work, your goals could be related to achieving a desired effect (e.g., increasing the understanding of quantum technology among politicians), creating new professional networks (e.g., better connections to civil servants in the Ministry of the Environment) or increasing your personal expertise (e.g., experience with organising a round-table discussion with researchers and organisational operators).

The time it takes to reach different goals varies and you should set goals for the short term or the long term depending on your working hours. Setting goals helps you choose one or more suitable method of interaction from the plethora of available methods.

If the goal is to bring perspectives into public discourse and develop your skills in popularised writing, science communication might be a natural method of interaction. A researcher focusing on science communication may strive to publish columns and perspectives in the news media and actively participate in the writing of research-related press releases.

However, if your goal is to expand your networks and gain a better understanding of policy-makers, you could strive to participate in workshops organised by knowledge brokers. In these kinds of events the researcher might get the opportunity to discuss with civil servants from ministries and listen to the views of researchers from other disciplines on the same issue.

You should choose the methods that best suit you and boldly try something new every once in a while.

One should not cling too much on the differences between disciplines

Branches of science differ from each other in terms of the kind of knowledge they produce. This can also affect the practical utilisation of the knowledge and the societal sector for which the knowledge is relevant. The following are examples of conceptions traditionally associated with the stakeholder connections of different disciplines:

- It is natural for technical and commercial disciplines to talk to business life,

- social sciences communicate smoothly with policy-making,

- pedagogy and behavioural sciences are orientated toward the school world and

- natural sciences fit well in innovation clusters.

At the same time, the idea that a certain discipline is suited for a certain kind of cooperation can narrow one’s view. In reality the opportunities for interaction are diverse regardless of discipline.

You should ponder without prejudice whether it would be beneficial for your research group or degree programme to try dialogue with NGOs or operators in business life. We encourage you to break borders and offer knowledge from your discipline to new sectors and fields – preferably together with other researchers.